Data is a Key Component of Enshittification Processes - but which part?

I was cleaning the bathroom yesterday (I have a lot of ideas when cleaning) and I started wondering to myself about the above. Enshittification, aside from being an amazing word, is a concept coined by Cory Doctorow to explain the decay in quality (as it were) of online services. The analyses of his that I have read do tend to focus on technology but since re-reading it a few weeks ago, I've started to see it everywhere, but also begun to question the role of my industry in it, as the somewhat plainer sibling to software engineering and the like.

When I was thinking about this in the bathroom, I initially thought that data was the driver, but maybe it's the fuel, and that fuel is available at different strengths (and power outputs).

Before cleaning I was watching a video on Instagram from an interesting Turkish creator, Tanner Leatherstein, who disassembles leather products to assess for quality, educating folks in the process - I learned about him from Andrea Cheong's great book Why Don't I Have Anything To Wear?, which also summarises a history of the enshittification of modern fashion. Leatherstein found a scam of new luxury brands appearing to open in Turkey, which wouldn't be a target for those brands at the moment, and reported them to Instagram and Shopify. As you might imagine, neither of those platforms did anything about the fraudulent accounts, instead telling him that only the brand owners could report that kind of fraud. Judging by the comments, Shopify have form in being unresponsive, and Instagram doesn't have a great track record (in anything?) either. But, I thought;

- Doesn't this damage their platforms? Perhaps only a tiny paper cut, but nonetheless damages their reputation as platforms for reliable and reputable e-commerce? Thousands of paper cuts are a problem, no?

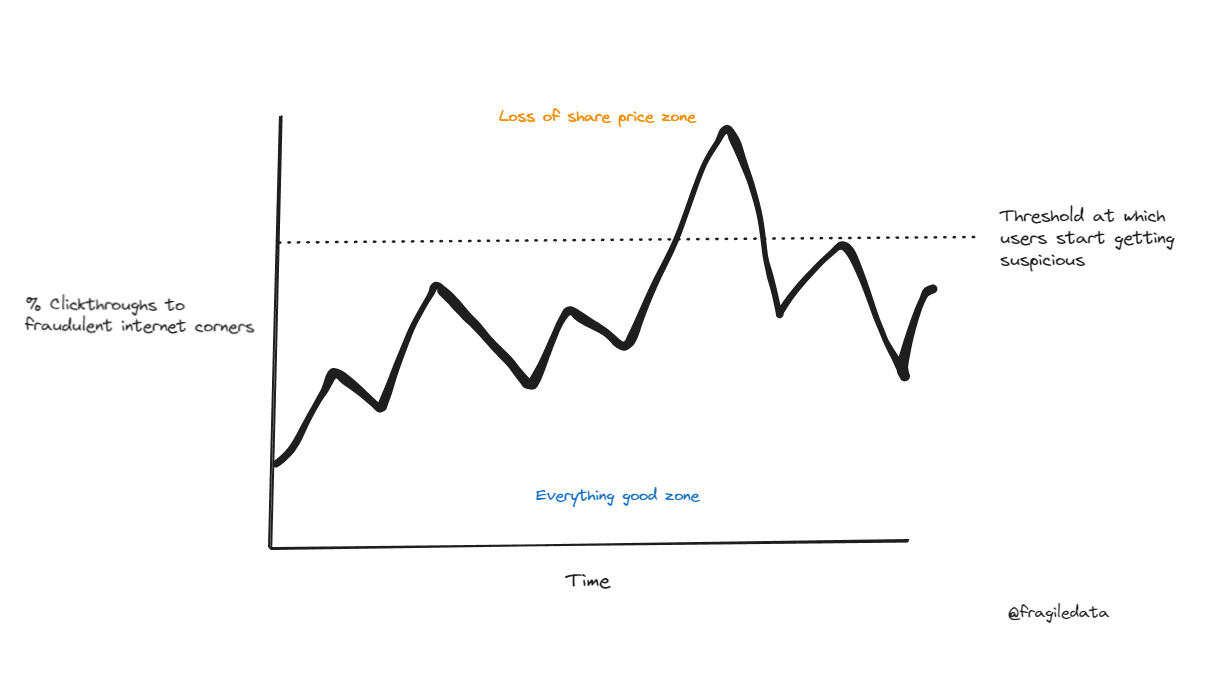

Leatherstein notes that these platforms are paid for by click throughs and interactions, and it doesn't really matter to them about the qualia of that click - it just has to happen, and they get paid. In a small way, this is a data problem - that's also a fraudulent click to Shopify and Instagram, surely. But in a big way it's also a data problem, which we can imagine on a graph.

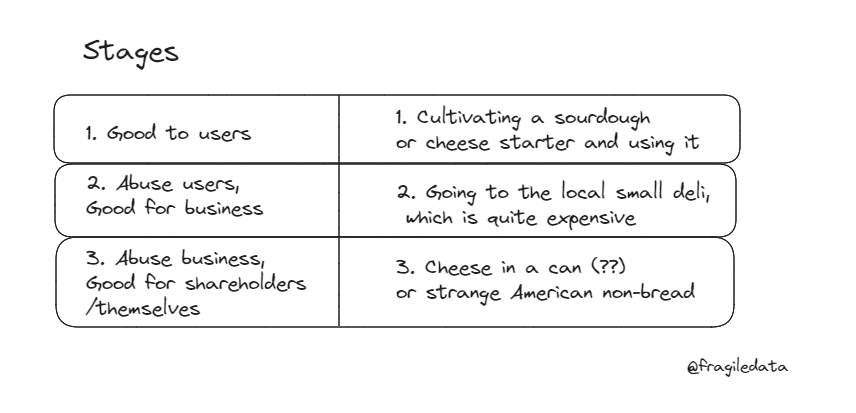

Doctorow's premise explains three stages in the Enshittification process, which I've compared here to the production of bread or cheese;

So where does data come in?

Before modernisation, there was essentially only stage 1. Things were useful to someone tangibly or not. Then, with industrialisation/ twentieth century, data and metrics started to appear in business, particularly for those who were disconnected to production. Finally, in twenty first century, it is almost impossible to start a business without data, because almost all businesses will have some online presence.

However, data didn't just appear because people started measuring things they couldn't necessarily police themselves. What's behind the emergence of data is the steamrollering imperative of optimisation, which uses data as fuel. Digital platforms, lacking other friction, are swimming in data with the potency of kerosene, blasting off into the night (of Generative AI at the moment). Enshittification however, identifies that these organisations don't actually know where they are going on the value map of reality - so if in doubt, optimise for shareholders/themselves, and screw the ecosystem of users or businesses on that platform. I find this not only explains what the hell is going south for so many of these digital platforms, but also for domestic products, because who is the canned cheese for?

I'm not placing the responsibility for the crumminess and decay of Enshittification at data's feet because that is a uniquely human thing to be responsible for, but I find it does provide an interesting vector to analyse the problem, and to understand organisations or approaches which have not fallen down the Enshittification hole.

Optimisation pressures tend to relate to speed, volume, and all the other words E.F Schumacher described as 'violent economics', which are also often the easiest things to measure. Alternatives comes from organisations who do not follow this path of least resistance to understand how data can inform their decision making, who can resist the default setting to just "optimise" things blindly. An small example from Customer Experience; some firms measure call volumes, others measure call backs or ticket re-openings. The former can encourage staff to simply get through calls or tickets quickly, rather than actually effectively solving the customer problem - the latter measure is trying to understand how many attempts the customer is making to solve an issue. The point of customer service is not getting through calls as quickly as possible, it is helping the customer as quickly as possible. Organisations which understand this will have better CSAT (oo a KPI!) scores than organisations which do not, and for some it might be enough to actually stake out a competitive advantage.

A larger example, in a somewhat more baffling way, could be drawn from the aforementioned world of fast fashion. I have a t shirt from H&M which is about 18 years old, which would be unheard of from any of their product line today. Back then, H&M didn't really know their shoppers, internet shopping for clothes wasn't so much a thing then, and they had to make a choice on particular styles and customer segmenting. Today's H&M has access to far more data by virtue of online shopping, where they can trace consumers purchases over time, collect reviews of their products, and make returns easy, giving them an awful lot of information about consumer response to their products. So, why

- do the clothes fit less well/patterns are poorer?

- are they made of shittier materials?

- are poorer value in terms of cost per wear?

Because fast fashion is the apex of 'optimisation as violent economics' above. H&M can release hundreds of products a year, get shirts to millions of people per year, but if no one actually likes this stuff, these are just numbers fainting in the newspaper next to big photos massive piles of discarded clothing in places like Chile and Ghana. But the photos make it to the newspapers, not the annual reports holding these firms to account - they are mostly focused on number of customers, stores and staff, as well as product line volumes and store targets and all that other easy stuff to measure (note that somehow the upstream supply chain, full of ethical monsters like forced labour, sweatshops and chemicals, apparently cannot be measured that well?).

I'm still thinking about data's role in this process but I'm leaning towards its role as the fuel. As such, data practitioners should include in their competencies enough critical thought to be able to question what the numbers are actually meant to represent. These are my earliest thoughts though, so hopefully I'll be able to follow up with this more over time.